Introduction

Can the human brain be understood as operating in a quantum state, and if so, do such quantum mind theories resonate with ancient Indian philosophical views of consciousness? This question bridges cutting-edge science and timeless spirituality. On one side, a minority of scientists have proposed quantum consciousness models – notably the Penrose–Hameroff Orch-OR theory – suggesting that consciousness arises from quantum processes in the brain. On the other side, Indian traditions like Advaita Vedānta, Sāṃkhya-Yoga, and Buddhism have rich, subtle understandings of mind and reality (e.g. concepts of ātman, puruṣa, and śūnyatā or emptiness). This article surveys scientific quantum mind theories and the Indian philosophical doctrines of consciousness, then explores how they parallel or diverge from each other. Specific examples (such as physicist Erwin Schrödinger’s Vedānta-influenced views) and contemporary dialogues (like the Dalai Lama’s engagements with scientists) will illustrate the cross-currents. We also discuss critiques from both sides. The goal is a structured, comparative understanding – not to conflate science and mysticism rashly, but to highlight where modern quantum ideas about consciousness and ancient insights might “shake hands,” and where they fundamentally differ.

Scientific Theories of Quantum Consciousness (Orch-OR and Beyond)

Quantum mind hypothesis: Unlike the mainstream view that brain activity is entirely classical (neurochemical and electrical signals in networks of neurons), quantum consciousness theories posit that quantum processes – with their non-classical features like superposition and entanglement – play an essential role in the mind. The most developed and debated example is the Orchestrated Objective Reduction (Orch-OR) model of Roger Penrose (mathematician-physicist) and Stuart Hameroff (anesthesiologist). According to Orch-OR, consciousness originates from coherent quantum computations in structures inside neurons called microtubules. These quantum states are hypothesized to evolve (under the Schrödinger equation) and then undergo an “objective reduction” (collapse) event connected to a quantum gravity threshold proposed by Penrose. In Orch-OR, countless microscopic tubulin proteins in microtubules act as quantum bits, and their orchestrated collapses produce discrete “moments” of conscious awareness. Penrose and Hameroff suggested this could solve the “hard problem” of consciousness by invoking new physics at the nexus of quantum mechanics and spacetime geometry. Notably, they argue that consciousness is non-computational and rooted in fundamental physical law, rather than being a mere emergent network effect. In their words, “consciousness plays an intrinsic role in the universe,” bridging brain processes with the basic structure of reality.

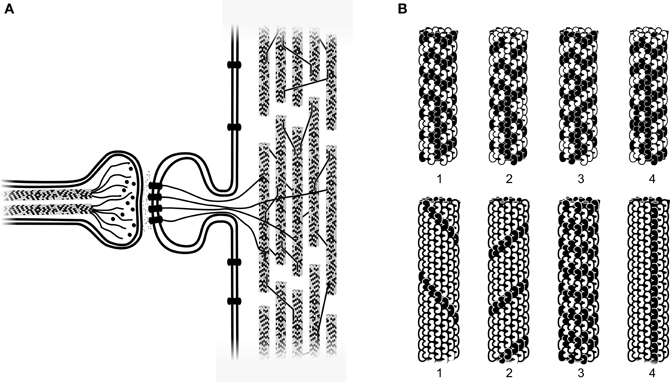

Figure: (A) Schematic of a neural synapse with microtubules inside the neuron’s dendrite receiving signals; (B) simulation of tubulin protein lattices in microtubules switching between states (black/white). In Orch-OR, tubulins can exist in quantum superposition of conformations and collectively encode qubits. An orchestrated collapse (“objective reduction”) of these states is proposed to trigger a moment of conscious experience. The theory thus assigns consciousness to quantum state reductions inside neurons, rather than emergent computation across classical synapses.

Evidence and challenges: Orch-OR is speculative and remains outside scientific consensus. One major challenge is the decoherence problem: the warm, wet brain seems hostile to delicate quantum states. In 1999, physicist Max Tegmark calculated that quantum superpositions in microtubules would decohere in an absurdly short time (~10^−13 seconds), far too fast to influence neuron firing (~10^−3 s). He concluded that brain processes should be treated as classical, and that proposals of quantum computing in neurons were implausible. Penrose and Hameroff responded by revising assumptions: they argued Tegmark’s model was oversimplified and that with more realistic parameters (e.g. smaller separation of superposed states, shielding by ordered water or proteins), microtubule coherence times could extend to 10^−5–10^−4 s, or even up to 10^−2–10^−1 s under special conditions. In principle, that is within the range of neural information processing. They likened the cellular environment to a laser, which can maintain coherent states at room temperature by pumping energy and order into the system. Recent interdisciplinary studies in quantum biology lend some plausibility: for instance, experiments have found quantum beat phenomena in photosynthesis and even collective quantum effects in microtubule protein networks at ambient condition. Hameroff and colleagues reported that certain anesthetics disrupt microtubule vibrations in ways that correlate with loss of consciousness (though causation remains unclear). These hints, however, fall far short of validating Orch-OR. Critics point out that no direct evidence of sustained brain-wide quantum coherence has been shown, and that the “quantum consciousness” idea is still highly speculative, even labeled pseudoscientific by some neuroscientists. At present, Orch-OR stands as a bold hypothesis under investigation, rather than an accepted theory.

Other quantum-mind ideas: Penrose and Hameroff are not alone in seeking a quantum basis for mind. Earlier, in the 1960s, Nobel laureate Eugene Wigner suggested that conscious observation causes wave-function collapse – the “von Neumann–Wigner interpretation” of quantum mechanics. In that view, the mind is non-physical and the only true measuring apparatus, without which quantum possibilities never crystallize into reality. (Wigner later moderated this stance under criticism, but the thought experiment “Wigner’s friend” remains a classic illustration of the measurement paradox.) More recently, physicist Henry Stapp has advanced a related model: he accepts that consciousness causes collapse of the brain’s quantum state, but instead of microtubules he locates the effect in the synapses, leveraging the quantum Zeno effect to explain how mind’s focus (attention) could hold brain states in a chosen pattern. Stapp’s approach still entails a kind of global “mind-like” selection of quantum brain states, differing in detail but echoing the theme that mind is deeply integrated into quantum processes. Other proposals range from Bohm’s holonomic brain theory (which likened brain memory to holographic interference patterns) to ideas in quantum cognition (using quantum probability models for cognitive phenomena – though usually without claiming the brain is literally a quantum computer). A recent line of inquiry by Matthew Fisher even speculates that certain nuclear spins in neural molecules (e.g. phosphorus in “Posner molecules”) might serve as biological qubits for memory, hinting nature could have found ways to preserve quantum information in the brain. All these models remain unproven. They face the dual challenge of scientific validation (hard evidence of quantum effects in neural processing) and theoretical clarity (explaining why quantum mechanics would give rise to subjective experience at all). Nonetheless, they open imaginative new fronts in the science of consciousness – and intriguingly, they often sound in tune with pre-modern intuitions that consciousness is more than classical matter.

Before examining those intuitions, we summarize: quantum consciousness theories like Orch-OR posit that the brain’s mind is not just an emergent neural network computation, but a macroscopic quantum state, entangled with fundamental physics. This invites comparisons with philosophical views that consciousness is fundamental or that the observer plays a key role in reality – ideas long discussed in Indian traditions. We now turn to those traditions to see what they say about mind, self, and the nature of reality.

Consciousness in Indian Philosophical Traditions

Advaita Vedānta: Ātman = Brahman (Universal Self)

Within Vedānta (the culmination of Vedic philosophy), the Advaita (“non-dual”) school espoused by Ādi Śaṅkara (8th cent. CE) holds a radical ideal: consciousness alone is the ultimate reality. The Upanishads (ancient scriptures) teach that the individual self (ātman) and the absolute reality (brahman) are identical – a doctrine encapsulated in the aphorism tat tvam asi (“That Thou Art”). In Advaita Vedānta, Brahman is defined as sat-cit-ānanda – absolute existence (sat), consciousness (cit), and bliss (ānanda). Consciousness is not a property of Brahman; Consciousness is Brahman – the sole, self-luminous essence underlying everythingiep.utm.edu. The empirical world of plurality (jagat) is said to be mithyā – not outright nonexistent, but a kind of illusion or misperception (like a mirage) superimposed on Brahman. Ātman, the innermost self of a person, is nothing less than Brahman itself, obscured by ignorance (avidyā) that makes us see ourselves as separate jīvas (souls). The famous verse often quoted is: “brahma satyam, jagan mithyā; jīvo brahmaiva nāparah” – Brahman alone is real, the world is illusory; the individual self is none other than Brahman. Thus, Advaita is a monistic idealism: only an undivided universal consciousness truly exists. All multiplicity (the myriad beings and objects) is ultimately a play of māyā (illusion or cosmic ignorance), comparable to dreaming or a projected shadow.

For Advaita, consciousness doesn’t emerge from matter – rather, matter (and mind) emerge from consciousness. Ordinary mental activities (thoughts, perceptions, etc.) occur in the mind (manas and buddhi, which Advaita views as subtle material instruments), but they are illuminated by the light of consciousness (Ātman). A Vedānta scholar explains: “the mind merely passes on the light of consciousness… it is one of the products of prakṛti or māyā, which has no consciousness inherent in it”. The true Self (ātman) is the witness of the mind, not itself an object or process. When, through spiritual knowledge (vidyā), one dispels ignorance, one realizes “ahaṁ brahmāsmi” (“I am Brahman”) – that one’s awareness at base is the infinite, all-pervading awareness. This realization (moksha, liberation) is said to bring freedom from the cycle of rebirth and suffering.

Historically, some of the architects of quantum mechanics were struck by the resonance of Vedānta with their own bizarre findings. Erwin Schrödinger, for example, was deeply influenced by Vedāntic ideas. Confronted by the puzzle of quantum mechanics – that reality might be “created by observation” and that multiple observers somehow see a synchronized universe – Schrödinger turned to the Upanishadic notion of a unitary consciousness. In What is Life? (1944) he mused that if each observer had their own separate world, we’d face an absurd multiplicity of divergent realities. The reasonable resolution, he wrote, was “the unification of minds or consciousnesses. Their multiplicity is only apparent, in truth there is only one mind. This is the doctrine of the Upanishads.” Schrödinger even ended some lectures by quoting “ātman = brahman” as the “second Schrödinger’s equation”. Such anecdotes illustrate how Advaita’s vision – a cosmic One Mind behind the illusion of many – anticipated a perspective some modern thinkers arrived at from grappling with quantum reality. (Of course, Advaita arrived at it through introspective and metaphysical inquiry, not particle experiments!)

In summary, Advaita Vedānta posits a universal consciousness as the sole reality, with the world and individual minds as appearances or reflections. It emphasizes the identity of the observer with the observed at the deepest level – since all is essentially Brahman. As we will see, this has interesting echoes in quantum interpretations that blur the line between observer and universe. But first, let us consider a very different Indian model of mind: the dualistic philosophy of Sāṃkhya and its sister tradition, Yoga.

Sāṃkhya and Yoga: Puruṣa-Prakṛti Dualism and the Yogic Mind

Sāṃkhya is one of the oldest Hindu philosophies (dating back to the early first millennium BCE) and provides the metaphysical foundation for Yoga (the system codified by Patanjali in the Yoga Sūtras circa 3rd cent. BCE). Unlike Advaita’s monism, Sāṃkhya is a dualistic cosmology: reality consists of two eternal, independent principles – puruṣa and prakṛti. Puruṣa is pure consciousness or spirit, while prakṛti is nature or matter (inert, insentient substance). Everything physical and mental – from gross matter to subtle body, mind, ego, intellect – is an evolution of prakṛti. Puruṣa, by contrast, has no physical attributes: it is an unchanging witness, beyond thought and sense, “absolute, independent, free… and impossible to describe in words” Puruṣa is essentially the Self, the conscious subject; prakṛti is the object (the entire observed world, including one’s mind and body).

Importantly, Sāṃkhya holds that there are many puruṣas (each conscious being has their own spirit), in contrast to Vedanta’s single Brahman. However, each puruṣa is of the same quality: an eternally liberated witness. Why then do we seem bound and subject to misery? Sāṃkhya explains that when puruṣa is in proximity to prakṛti, prakṛti’s equilibrium is disturbed and it begins to evolve – unfolding into intellect (buddhi), ego (ahaṁkāra), mind (manas), the senses, and the elements. The puruṣa, though itself inactive, becomes reflected in the buddhi (intellect), and thereby appears to be an individual embodied consciousness (called jīva). In truth, puruṣa never acts; it merely witnesses prakṛti’s dance. But due to ignorance, the puruṣa falsely identifies with the body-mind complex and experiences suffering. The goal of Sāṃkhya-Yoga is thus to disentangle the knower from the known: to realize that “I am puruṣa, not the body, not the mind,” thereby achieving kaivalya (isolation of consciousness) or liberation. At liberation, puruṣa remains as pure awareness, and prakṛti falls back to quiescence having served its purpose.

The Yoga school, as described in Patanjali’s Yoga Sūtras, adopts this Sāṃkhyan dualism and provides a practical methodology to achieve that isolation. Patanjali defines yoga famously as “yogaś citta-vṛtti-nirodhaḥ” – “Yoga is the cessation of the fluctuations of the mind.” In other words, yoga is the stilling of the mental whirlpools (vṛttis) in consciousness (citta) to reveal the true self as . The citta (mind-stuff) in Yoga consists of intellect, ego, and mind – essentially prakṛti’s subtle evolutes. When thoughts, desires, and identifications are silenced through meditation and ethical discipline, the seer (draṣṭā) rests in its own nature as pure witness. The Yogic journey is thus one of inner observation: the practitioner cultivates a “witnessing presence”, observing mental phenomena without attachment. This sakshi bhava (witness attitude) is explicitly encouraged: one learns to see thoughts as passing clouds, not as self. Ultimately, in the state of samādhi (complete absorption), the mind’s activities cease, and puruṣa stands alone in its pure consciousness, completely separate from prakṛti. Patanjali describes this as the attainment of viveka-khyāti (discriminative knowledge) – the clear insight that puruṣa is distinct from all phenomena.

How does this relate to quantum mind notions? We can draw a thematic parallel: Sāṃkhya-Yoga posits a duality of conscious observer vs. observed material system. Consciousness (puruṣa) is an independent fundamental category, irreducible to matter – somewhat akin to how a strong interpretation of quantum consciousness suggests mind isn’t reducible to classical neural activity. In quantum measurement theory, one may analogously speak of the observer and the observed, where certain interpretations treat the observer’s awareness as separate from physical wavefunctions. Sāṃkhya’s notion that puruṣa’s mere presence “collapses” prakṛti from latent equilibrium into an active state is evocative (metaphorically) of how an act of observation in quantum mechanics “collapses” a wavefunction into a definite state. Of course, Sāṃkhya’s context is spiritual, not experimental; the “collapse” here is prakṛti manifesting the cosmos for puruṣa’s experience, not a lab measurement. Nonetheless, both conceive a two-tier reality: an unchanging knower and a changeful known.

It’s also worth noting that Sāṃkhya and Yoga, like most Hindu traditions, accept rebirth and subtle planes of reality. The puruṣa can transmigrate, and the mind (as part of prakṛti) carries impressions (saṁskāras). A quantum theorist might speculate: if consciousness were quantum-mechanical, could “information” (or quantum state) carry over after bodily death? Hameroff at times speculated about microtubule states persisting or “quantum soul” ideas, but these remain speculative and controversial even within Orch-OR.

In sum, Sāṃkhya-Yoga sees consciousness as an eternal, plural plurality of witnesses (puruṣas) utterly distinct from matter, and the mind as part of material nature (prakṛti) and inherently insentient. Conscious experience arises only when puruṣa is associated with a mind, much as a lamp illumines a field. This dualism underscores a sharp mind/matter divide reminiscent of Cartesian dualism (though Sāṃkhya is non-theistic and posits many souls). Its emphasis on the observer (puruṣa) and the process of observation (dṛśya, the seen) finds a curious parallel in the quantum discourse about the role of observation. The Yoga practice of stilling the mind to experience “oneness” or union (ironically, union of individual self with universal Self in some interpretations, despite Sāṃkhya’s plural puruṣas) also resonates with descriptions of holistic or unitary consciousness sometimes reported by quantum-minded thinkers. For example, advanced meditators often report a dissolution of the subject-object division, a state where the observer “merges” with the observed. This is reminiscent of Schrödinger’s Vedantic insight of one mind, though classical Yoga would interpret it as the puruṣa experiencing itself apart from all empirical distinctions.

Buddhism: Mind, No-Self, and Emptiness

Buddhist philosophy offers yet another perspective, in many ways more subtle and skeptical about metaphysical absolutes. Buddhism (5th cent. BCE onwards) famously denies the existence of any permanent soul or ātman (anattā or anātman doctrine). Instead, a person is understood as a transient aggregation of five skandhas (aggregates): form (physical body), feelings, perceptions, mental formations, and consciousness. Even consciousness (vijñāna) is not a unitary enduring entity – it is a stream of momentary cognitions, conditioned by sense-organ and object. The Buddha compared it to a flame that appears continuous but is actually a rapid series of arisings and ceasings. Thus, there is no thinker behind thought, no independent “observer self” separate from the process of knowing. The five aggregates are all not-self (anattā), meaning none of them is an unchanging essence or “I.” Consciousness arises dependent on conditions (contact of sense organ and object, etc.) and ceases when those conditions cease. In modern terms, we might say Buddhism presents a kind of process philosophy of mind: only causally-linked mental events, no fixed “mind substance.”

A key Buddhist contribution is the concept of emptiness (śūnyatā), developed especially in Mahāyāna Buddhism by Nāgārjuna (2nd cent. CE) and others. Emptiness is often misunderstood; it does not mean nothing exists. Rather, it means that things (dharmas) lack any svabhāva (intrinsic, independent existence). All phenomena exist relationally or dependently (pratītya-samutpāda, dependent origination). For example, a chair exists only due to a multitude of causes (wood, carpenter, molecules) and conceptual designations – it has no independent chair-essence. The same applies to the self: what we call “person” is a convenient label on a flux of body and mind elements. Buddhist philosophers assert that no phenomenon – whether material or mental – exists in isolation; identity is meaningful only within interdependence. As the Dalai Lama concisely puts it, “No phenomenon exists with an independent or intrinsic identity… There are no subjects without objects to apprehend them, and no objects without subjects”. This view dissolves the hard boundary between observer and observed as mutually defining. It intriguingly foreshadows relational interpretations of quantum mechanics, where properties of particles are not absolute but relative to interactions (and the idea that the observer/measurement apparatus and observed system form one whole). Indeed, the Dalai Lama has remarked that “Buddhist philosophy and quantum mechanics can shake hands on their view of the world” – referring to how both suggest that what we perceive as solid reality is, at the fundamental level, devoid of fixed essence and arises in dependence on observation and context.

Within Buddhism, multiple schools offered different models of mind:

The Abhidharma scholastics broke experience into dozens of mental factors and saw consciousness as a series of momentary dharmas (phenomena).

The Yogācāra (Cittamātra) or “Mind-Only” school (circa 4th cent. CE) took a more idealistic turn, asserting that what we take to be external reality is actually a construction of mind; mind (citta) is the ultimate reality. They introduced the concept of a deep “storehouse consciousness” (ālayavijñāna) that contains karmic seeds and generates the illusion of a world. Superficially, Yogācāra might sound akin to Berkeleyan idealism or even some quantum “consciousness creates reality” notions. For instance, one Yogācāra tenet holds that external objects do not exist apart from perception – “if there is cognition of it, something exists; if there isn’t, it doesn’t.” This echoes (in a very different ontological framework) the idea that an unobserved quantum state has no definite reality until observed. However, Yogācāra still does not posit a permanent soul – the mind itself is an evolving flow, just a more fundamental aspect of reality than matter.

The Madhyamaka school (of Nāgārjuna) meanwhile insisted that even consciousness is empty of inherent existence. They introduced the two truths framework: an ultimate truth – that ultimately all phenomena are śūnya (empty of self-nature) – and a conventional truth – that relatively, in everyday experience, things do appear and function (cause and effect, ethics, etc., remain valid). One must not deny the conventional reality, or one falls into nihilism; but one must not reify it either, or one falls into fundamentalism. The Dalai Lama analogizes this to physics: classical Newtonian physics is conventionally true in its domain, while quantum physics reveals a deeper ultimate truth of uncertainty and relational existence. Neither contradicts the other if kept to their domain – just as the Buddhist two truths don’t violate each other.

In Buddhism, the mind is a dynamic, interdependent process, and awareness (while profoundly important in Buddhist practice) is not something magical or apart from causality – it obeys natural laws of dependent origination just like physical events. There is a famous dialogue in Milinda Pañha where the monk Nāgasena says “mind and matter are like two sheaves of reeds propping each other up,” illustrating their codependence. Unlike Sāṃkhya’s puruṣa or Vedānta’s ātman, Buddhism’s consciousness is not an independent witness outside the world; it is part of the world’s fabric of conditions. However, in meditation, Buddhists do cultivate a witnessing faculty in the sense of mindfulness – observing thoughts and sensations without attachment – somewhat analogous to Yoga’s approach. Advanced meditation can lead to experience of non-duality (especially in Mahāmudrā or Dzogchen traditions of Tibetan Buddhism). In such states, the usual subject-object split is transcended, giving way to what is described as a boundless, lucid awareness. Some interpreters liken this to a direct insight into the “quantum foam” of experience where conventional distinctions dissolve – though Buddhists themselves frame it as realizing the empty, luminous nature of mind. There is even a term “rigpa” in Dzogchen, meaning the primordial awareness that is empty and cognizant, present in all beings. While not an ego or soul, it is in a sense a fundamental aspect of reality, reminiscent of how some quantum consciousness proponents speculate consciousness might be a fundamental property of the universe.

In summary, Buddhism denies a permanent soul and instead analyzes consciousness as a contingent process, with the ultimate truth that both observer and observed are empty of inherent existence. Yet, through understanding emptiness, one can radically alter one’s experience of reality – achieving liberation from ignorance (which in Buddhism is the false belief in independent selves and things). The Buddhist view challenges any simplistic equation of “consciousness = cosmic fundamental” because it sees that idea as just another concept to be deconstructed. And yet, the experience of an enlightened mind – a non-dual, all-connected perspective – has often been poetically compared to a kind of “merged” consciousness that resonates with holistic or unified descriptions in other traditions.

Having outlined these four perspectives – Advaita’s one universal Self, Sāṃkhya/Yoga’s conscious dualism, and Buddhism’s no-self but all-relational mind – we can now draw comparisons between them and the quantum consciousness theories. Do Penrose and Hameroff’s ideas (and similar quantum mind notions) echo ancient ideas like Brahman or puruṣa or emptiness? In some respects, yes: there are striking parallels in how each side grapples with the mind-matter relationship and the role of the observer. In other respects, no: the motivations and conclusions can differ profoundly. Below, we examine these resonances and contrasts, organized by key themes.

Parallels Between Quantum Models and Indian Philosophies

1. Consciousness as Fundamental vs. Emergent: Both Orch-OR and several Indian philosophies converge on the intuition that consciousness is not a by-product of classical matter, but is rooted in the fabric of reality. Penrose and Hameroff explicitly argue that consciousness arises from quantum processes linked to fundamental spacetime geometry, implying it’s ingrained in the universe’s structure. In their view, mental phenomena aren’t just chemical epiphenomena; they tap into deeper physical laws – suggesting a proto-conscious aspect of the cosmos. This finds a strong echo in Advaita Vedānta, where Consciousness (Brahman) is the ground of all being. Just as Orch-OR posits an ontological presence of consciousness at the Planck-scale physics level, Advaita posits consciousness at the metaphysical absolute level. Both assert, in effect, that mind is woven into the very fabric of reality, not an accident. Likewise, Sāṃkhya-Yoga considers consciousness (puruṣa) as an eternal principle parallel to matter – a fundamental category of existence, not emergent from material complexity. And some interpretations of Buddhism (particularly in Mahāyāna) speak of an intrinsic “Buddha-nature” or luminous awareness present in all beings, which, while not a creator of the world, is a fundamental reality to be realized. However, a caveat: classical Buddhism would say mind has primacy in experience (“Mind is the forerunner of all things,” as the Dhammapada opens) but not necessarily that mind is an irreducible substance of the universe – ultimately even mind is empty of self-nature. Thus, a quantum theorist might lean towards panpsychism (the idea that consciousness is a fundamental feature of matter, perhaps at the level of quantum events). Interestingly, panpsychist ideas are increasingly discussed in philosophy of mind and resonate with Vedānta and possibly with a quantum view of ubiquitous proto-consciousness. To summarize this parallel: Orch-OR and Advaita both treat consciousness as deeply fundamental, not an emergent afterthought; Sāṃkhya agrees, placing consciousness as co-fundamental with matter; Buddhism values consciousness but ultimately dissolves its claim to fundamentality (no ātman).

2. Mind-Matter Relationship (Dualism, Monism, or Non-dualism): Quantum consciousness theories fundamentally challenge the classic Cartesian division by suggesting mind and matter are interwoven at the quantum level. In Orch-OR, brain matter doesn’t produce mind by itself; rather, quantum matter and mind are two sides of the same coin during the collapse process – the quantum state reduction is simultaneously a physical event and a conscious event. This brings to mind (pun intended) the Vedāntic view that mind and matter are just two levels of description of Brahman: “matter” being Brahman seen through ignorance (Maya), and mind (ātman) being Brahman as the witnessing self. In Vedānta, when one truly knows Brahman, the distinction vanishes – mind and world are one reality (Brahman), only mistakenly seen as separate. Penrose’s conjecture that a piece of spacetime can undergo a quantum collapse that is also a conscious thought is almost a scientific re-articulation of a non-duality: it implies the physical process is the mental event viewed differently. Meanwhile, Sāṃkhya sets up a clear dualism – puruṣa versus prakṛti – which might seem at odds with a unified quantum view. However, Sāṃkhya also states that prakṛti (matter, including the brain) is jaḍa (insentient) and cannot be aware without puruṣa; Orch-OR similarly implies classical brain matter is “insentient” without quantum reduction events injecting conscious moments. In both, raw matter needs consciousness to light it up. Sāṃkhya would differ in saying puruṣa never interacts or changes (it’s just a witness), whereas quantum models imply a two-way interaction (quantum state is affected by conscious collapse and vice versa). Yoga, inheriting Sāṃkhya’s dualism, is methodologically dualist (separate the seer from seen), but experientially, samādhi blurs this line – many yogis describe an experience of oneness or unity consciousness when the mind is stilled. That is arguably a monistic experience emerging from dualistic practice. Buddhism offers the middle way: neither monism nor dualism, but a kind of non-duality. Mind and matter are distinct conceptually (nāma-rūpa), but inseparable in existence (like two sides of a coin). Conventional reality sees minds here and objects there; ultimate reality sees a contingent web with no hard borders. This aligns well with relational quantum interpretations where the dichotomy breaks down – you don’t have a totally separate observer and observed; rather the act of observation is an interaction binding them. Both Madhyamaka Buddhists and quantum physicists ask: when does the observed system become “real”? In Buddhism, only within a conventional frame; ultimately it’s empty. In quantum physics, only upon interaction/observation; prior to that, the state is indeterminate (empty of definite properties). Thus, both Buddhism and quantum theory reject naive realism – the view that objects possess solid, observer-independent existence in the way they appear. An example: the Dalai Lama noted that “from the perspective of the ultimate truth, things and events do not possess discrete, independent realities… their ultimate ontological status is ‘empty’”, which he compared to the quantum view that unmeasured phenomena don’t have definite properties.

3. The Role of the Observer: One of the most intriguing crossovers is how both modern physics and Indian thought grapple with the observer. In quantum mechanics, especially in interpretations like Wigner’s, the conscious observer is special – the collapse of the wavefunction is said to happen when a conscious mind registers the observation. Even though this view is not widely held among physicists today (it’s considered problematic and “solipsistic” by Wigner’s own later admission), it highlights the puzzle that the act of observation seems to bring reality into definiteness. Now consider Indian perspectives:

In Advaita Vedānta, the ultimate observer is Brahman itself, looking out through all eyes. The world exists as a projection on consciousness; when one realizes Brahman, observer and observed collapse into unity. There is a famous analogy: Brahman is like a screen and the world is a movie projected upon it; only the screen is real. In a sense, the observer (Self) creates the observed world by misidentification – much as in quantum physics the observer “creates” the outcome by the act of measurement. An Advaitin might say the universe manifests because the one Consciousness observes itself as “other” through the funhouse mirror of māyā. This is of course a mystical take, not a scientific one, but it poetically resonates with the measurement paradox.

In Sāṃkhya, puruṣa is the passive observer. It doesn’t create prakṛti, but without puruṣa, prakṛti remains unmanifest, “like a dancer without an audience.” The presence of the observer is what makes the universe unfold (just as a quantum state might stay in superposition until interaction). Moreover, Sāṃkhya holds that bondage is only due to puruṣa’s misidentification with prakṛti; the moment the observer truly separates (knows “I am witness, not actor”), the show ends for that puruṣa – prakṛti’s purpose (to provide experience for the puruṣa) is done, and it attains quiescence. This is analogous to the idea that once knowledge (observation) happens, the uncertainty is resolved. Sāṃkhya’s multiple puruṣas correspond to multiple streams of consciousness – somewhat like multiple “observers” in physics. In quantum mechanics, observers are not privileged as individuals (the theory doesn’t say who collapses what if two people observe the same event – leading to thought experiments like Wigner’s friend). Schrödinger’s one-mind resolution (influenced by Vedānta) was to suggest ultimately there’s only one observer (Brahman) behind all, to avoid the paradox of divergent observations. Sāṃkhya would not go that route (it insists on plurality of souls), which might be more akin to a “many-minds” interpretation.

Yoga practice makes the role of observer very explicit: one cultivates the “drashta” (seer) position, witnessing mental phenomena. In neuroscience terms, this is meta-cognitive awareness. Interestingly, some neuroscientists have associated this with specific brain patterns (e.g. meditation leading to synchronized gamma oscillations) and one might speculate if this corresponded to more coherent brain states – perhaps in a fanciful way, more quantum-like ordered states. While that’s conjecture, the subjective report of deep meditation is often a feeling of merging with the observed object (non-duality).

Buddhism offers a clear statement: “there are no objects without subjects, and no subjects without objects”. This is not to elevate the subject as a metaphysical principle (since subject and object are both empty), but it underscores a relational ontology: observer and observed arise together. This is strikingly similar to relational quantum mechanics or participatory realist views (Wheeler’s “it from bit”) where an observer and system define each other’s state through interaction. Buddhism also directly addresses the observer effect but in psychological terms: our very act of perception co-creates the world we experience (through mental imputation). In quantum physics, an observer’s choice of measurement determines what aspect of a system is realized (wave or particle, for example). Some have drawn parallels here with Nāgārjuna’s two truths: at the conventional level, cause and effect and observers exist (like choosing a measurement yields a result), but ultimately, when you analyze deeply, you can’t find a fixed point where “observation” or “cause” resides – it’s empty.

In summary, the observer is central in both arenas: quantum theorists worry about what consciousness does to reality, and Indian sages have long claimed consciousness shapes reality. In the Indian context, this often takes a spiritual form (e.g. “with purified vision, a yogi sees Brahman everywhere and the world as illusion” or “a Buddha sees the illusory nature of phenomena”). In the scientific context, it’s a puzzle of measurement. They shouldn’t be conflated, but it’s fascinating that both end up rejecting a strictly object-centric worldview and give the observer an active or constitutive role.

4. Unity and Non-locality: A frequent theme in comparing quantum physics to Eastern thought is wholeness. Quantum entanglement shows that particles once interacted can have instantaneous correlations no matter the distance – suggesting the universe is deeply non-local and interconnected. David Bohm spoke of an “implicate order” tying everything. Eastern mystics often emphasize a holistic unity of existence as well. Advaita Vedānta outright says only a single, undivided reality exists – Brahman – and that perceiving oneself as separate is a delusion. This aligns with the spirit of non-local quantum interconnectedness: the idea that at a fundamental level, separation is illusory. Schrödinger, after all, used Vedānta to answer how multiple observed worlds stay in sync – by positing one mind behind them. In modern terms, one could whimsically say “the wavefunction of the universe” is the one Brahman, and our individual minds are like collapsed branches that mistakenly see themselves apart. (Schrödinger indeed said multiplicity is Māyā, a deception) Buddhism also, in Mahāyāna, speaks of interconnectedness – e.g. the Avataṁsaka Sūtra’s metaphor of Indra’s Net, where each jewel reflects all others, often likened to a hologram or a network of entanglement. When the Dalai Lama studied quantum physics, he found it “filled him with pride” that Nagarjuna’s idea of emptiness anticipated a relational reality where things have no independent existence. Bell’s theorem and experimental violations of Bell’s inequalities (demonstrating entanglement’s reality) have even been poetically compared to a physical vindication of “all is one” – though one must be careful: quantum entanglement connects specific particles, not a universal mind. Still, it shows our classical intuition of separateness is incomplete. In Yoga, the peak experience is samādhi, described as a state of oneness or integration (“yuj” root of yoga means to yoke or unite). In nirbīja samādhi (seedless samādhi), distinctions of observer, act of observing, and observed object collapse entirely – a unity of pure consciousness is experienced. This is akin to descriptions of mystical union in many traditions, and interestingly parallels accounts from some physicists who had quasi-mystical feelings about the unity of the cosmos (e.g. Einstein’s cosmic religious feeling, or Pauli and Jung’s search for unified psyche-physics principles). Non-locality in quantum theory also resonates with the idea in some Indian texts that consciousness is not confined to the body. Vedānta would say your real Self is all-pervasive (brahman is everywhere), and Yogic siddhis (powers) even include “remote viewing” and such, implying mind can act at a distance (anecdotal, not scientific, of course). The panpsychist strands of quantum mind theories entertain that consciousness might be a field present throughout space (e.g. Penrose speculated consciousness is linked to space-time micro-geometry, thus likely universal). Orch-OR’s suggestion that consciousness is tied to basic space-time geometry hints at a unity – since space-time underlies all matter, consciousness would pervade in principle. This can be (loosely) compared to Vedānta’s all-pervasive Brahman or to certain Tibetan Buddhist concepts like the “clear light mind” that pervades the continuum of existence.

To crystallize the comparisons between quantum consciousness theories and Indian philosophical systems such as Advaita Vedānta, Sāṃkhya-Yoga, and Buddhism, we can explore the main aspects thematically:

Ultimate Nature of Consciousness

In the Orch-OR theory of quantum consciousness, consciousness is viewed as fundamental and non-classical, rooted in spacetime geometry itself. It is not an emergent epiphenomenon of neural complexity, but a basic feature of the universe—an intrinsic property of quantum processes, particularly those occurring in neuronal microtubules.

Advaita Vedānta also posits that consciousness is ultimate. It identifies Brahman as sat-cit-ānanda—pure being, consciousness, and bliss. The individual self (ātman) is declared to be non-different from Brahman. Consciousness is not a product of anything; rather, it is the sole unchanging reality, and the apparent world is only a projection upon it.

In contrast, Sāṃkhya and Yoga describe consciousness as puruṣa—eternal, many in number, and fundamentally distinct from matter (prakṛti). Puruṣa is pure, unchanging witness-consciousness. It is not produced by prakṛti, nor is it emergent. It simply illuminates the activity of the mind.

Buddhism, particularly in the Madhyamaka tradition, rejects the idea of a single eternal consciousness (anātman). Instead, it views consciousness (vijñāna) as a transient, conditioned process—an impermanent stream devoid of self-nature. Even the mind has no intrinsic existence; it arises dependently. However, some Mahāyāna schools, such as Yogācāra, speak of a luminous, ever-present foundational consciousness or Buddha-nature, though even this is said to be empty of inherent existence.

Mind–Matter Relationship

The Orch-OR theory suggests a dual-aspect monism, where physical processes (quantum computations) and conscious experiences are two facets of one underlying reality. The brain is not a classical machine but a quantum system entangled with consciousness. The collapse of a quantum state in microtubules is simultaneously a physical and a mental event.

In Advaita Vedānta, the relationship is idealistic monism. Matter, body, and brain are all seen as māyā—an illusory projection upon consciousness. Mind and senses are not inherently conscious; they are enlivened by the reflection of the ātman. Consciousness alone is real, and what appears as matter is only its appearance in ignorance.

Sāṃkhya-Yoga presents strict dualism. Consciousness (puruṣa) and matter (prakṛti) are fundamentally different. Mind, intellect, and ego are evolutes of matter and are inherently unconscious. Puruṣa does not emerge from the brain or interact causally, but it illuminates prakṛti’s manifestations. Yoga aims to quiet the mental fluctuations (citta-vṛtti-nirodha) so puruṣa can be realized in its pure, detached state.

Buddhism maintains that mind and matter are co-dependent. Rather than being distinct substances, they are mutually conditioned processes. The conventional world includes both mental and physical events, but neither exists independently or absolutely. There is no dualism of soul and body; both are aggregates lacking inherent self-existence. Reality, in this view, is non-dual in the sense that subject and object arise only in relation to each other.

The Role of the Observer

In quantum theories like Orch-OR, the observer plays a crucial role. Some interpretations suggest that a conscious observer collapses quantum possibilities into definite outcomes. Orch-OR ties moments of consciousness directly to orchestrated collapses in the brain. Wigner even suggested the mind is the only true measuring device, essential to defining physical reality.

In Advaita Vedānta, the conscious self—the ātman or Brahman—is the ultimate seer (draṣṭṛ). The world exists as an object of this consciousness. The observed world and the observer are ultimately not two. When the jīva realizes its identity with Brahman, it recognizes that the world was never truly separate.

Sāṃkhya maintains that puruṣa is the eternal observer—completely inactive, yet necessary for prakṛti to manifest its functions. The presence of the puruṣa allows experience to arise. Liberation occurs when puruṣa ceases identification with prakṛti and abides in its pure witnessing nature. Yoga builds on this by encouraging cultivation of the witness attitude through meditation and detachment from mental fluctuations.

Buddhism, on the other hand, denies an independently existing observer. The sense of a separate self is the result of a compounded process involving physical and mental aggregates. Observation is real, but the observer is not an ontological entity—it is a function. Buddhism emphasizes mindfulness and awareness, but also asserts that observer and observed co-arise; neither has any independent reality. The act of observation is seen as a transient event in a stream of experience.

Unity vs. Plurality

In Orch-OR, the theory does not explicitly propose a single, universal consciousness. However, by connecting consciousness to the fundamental structure of spacetime, it hints at a possible continuity or field-like aspect of consciousness that pervades all brains. Some thinkers have speculated that entanglement and non-locality may point toward a deeper unity, even invoking ideas like Schrödinger’s “One Mind.”

Advaita Vedānta firmly posits such unity. There is only one consciousness—Brahman. The multiplicity of selves is an illusion caused by ignorance. Individual minds are like reflections of one moon in many water pots. When ignorance is removed, all distinctions disappear, and the truth of one undivided Self is realized.

In contrast, Sāṃkhya and Yoga assert the plurality of puruṣas. Each sentient being has its own independent consciousness. While all puruṣas are of the same nature—pure, unchanging witnesses—they remain distinct. Even in liberation, each puruṣa attains its own state of isolation (kaivalya).

Buddhism takes a more nuanced view. Conventionally, there are many mind-streams and sentient beings. Ultimately, however, all such distinctions are seen as empty. The question of one or many becomes irrelevant from the standpoint of emptiness. In Mahāyāna, the idea of universal interdependence (e.g., Indra’s Net) implies a profound unity—not of identity, but of interbeing. Still, Buddhism avoids asserting either monism or pluralism in ontological terms, focusing instead on dependent origination.

(Table: Comparison of key concepts in quantum consciousness theories and Indian philosophies. Sources: Orch-OR theory pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.govpubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov; Advaita Vedānta iep.utm.eduscience.thewire.in; Sāṃkhya/Yoga en.wikipedia.orgyogapedia.com; Buddhism scienceandnonduality.comen.wikipedia.org.)

Critiques and Reflections: Bridging Science and Spirituality

The apparent resonances outlined above are fascinating, but they warrant a critical examination. Both scientists and scholars of religion/philosophy have cautioned against drawing simplistic equivalences between quantum physics and spiritual concepts – a trend sometimes pejoratively called “quantum mysticism”. Here, we consider some critiques from multiple angles:

Scientific Skepticism: The majority of neuroscientists and physicists remain unconvinced that quantum effects play a significant computational role in the warm, wet brain. The Orch-OR theory, for instance, has been critiqued on many fronts: Penrose’s appeal to Gödel’s theorem and non-computability is widely viewed as unpersuasive, and Hameroff’s microtubule proposals are seen as lacking direct evidence. Max Tegmark’s calculation that neural decoherence is quasi-instantaneous led many to conclude that “the brain should be thought of as classical” and that quantum brain theories are “at best considered wrong, at worst pseudoscience.” (Quote from a consensus view expressed informally by physicists.) While recent quantum biology findings (like long-lived coherence in photosynthetic complexes) show that non-trivial quantum states can exist in warm biology, the brain’s case is unproven. Without empirical confirmation – e.g. detecting brain-wide entanglement or quantum interference influencing cognition – quantum consciousness remains a hypothesis in search of data. Critics also note that even if microtubules had quantum states, it’s a leap to identify those with consciousness. The “leap of faith” – equating a specific physical process with the subjective mind – can seem reminiscent of vitalism (seeking a special substance for life). Some scientists feel Orch-OR merely shifts the mystery (from neurons to microtubules or Planck-scale collapses) without truly explaining consciousness. As such, linking it with ancient philosophy might put the cart before the horse: we risk using speculative science to justify metaphysics, or vice versa.

Philosophical Critiques: Philosophers of mind often point out that even a successful quantum brain theory would not automatically solve the hard problem of consciousness (why physical processes have first-person experience at all). It would be a new correlation at best. The Indian traditions, meanwhile, were never trying to explain consciousness in a mechanistic way – for them consciousness was either irreducible (Atman/Purusha) or a conditioned flow to be understood experientially (Buddhism). The goals differ: science seeks explanation and predictive power; spiritual philosophies seek meaning and liberation from suffering. So one must be careful not to conflate categories. For example, Advaita Vedānta’s Brahman is not an empirical hypothesis but a metaphysical postulate validated (for adherents) by contemplative insight. To say “Brahman = quantum vacuum” or “brahman = unified field” is more poetic than rigorous – it might inspire interesting thoughts, but Brahman in Advaita is beyond measurement or concept, whereas a quantum field is a precise physical entity. Buddhist emptiness too is a philosophical doctrine about the contingent existence of phenomena, not a claim about particles per se. When Buddhists say “form is emptiness” in the Heart Sutra, they’re not talking about atomic structure, but that form has no independent essence. Some New Age interpretations stretched this to say “Physics finds mostly empty space in atoms, thus matter is empty – Buddhism knew it!” – a rather superficial comparison (the “emptiness” in physics is literal vacuum space; in Buddhism it’s a lack of inherent identity). Scholars like the Dalai Lama, who is enthusiastic about science, are careful to note parallels are mainly analogies. He says, for instance, that quantum mechanics challenges naive realism similar to how Madhyamaka does, but he doesn’t claim they are the same theory.

“Quantum Mysticism” concern: Historically, books like Fritjof Capra’s The Tao of Physics (1975) and Gary Zukav’s The Dancing Wu Li Masters drew popular comparisons between quantum physics and Eastern mysticism (Taoism, Buddhism, Vedanta). While inspirational to many, they were criticized by some scientists for glossing over technical details and implying a premature convergence of science and mysticism. There is a risk of confirmation bias – seeing agreement where each tradition’s language is actually quite different in meaning. For example, the phrase “All is one” could stem from: (a) a rigorous derivation in quantum field theory that all particles are excitations of one field, or (b) a mystical intuition in meditation of unity. Both are valid in context but not identical. Serious comparativists (like physicist David Bohm in dialogue with Krishnamurti, or Francisco Varela combining neuroscience with Buddhism) have emphasized that we must respect the distinct methodologies: science relies on third-person observation and mathematical theory; spirituality often relies on first-person introspection and philosophical reasoning. Each can inform the other (e.g. mindfulness practices have influenced cognitive science, quantum logic has spurred philosophers to revisit Aristotle’s logic), but we shouldn’t merge them hastily.

Differences among the Indian traditions: We lump “Indian philosophies” together, but Vedānta, Sāṃkhya, Yoga, Buddhism have significant disagreements. When comparing to quantum ideas, one might selectively pick aspects that fit. For instance, Vedānta’s Brahman arguably aligns more with a panpsychist or idealist picture (consciousness fundamental), whereas Buddhism’s no-self and process ontology could align with a process physics or information-centric picture (where no static entities exist, only interactions – some physicists like John Wheeler have proposed “it from bit” – the universe fundamentally comprised of information events, not things, which is curiously resonant with Buddhist ontology of dharmas). Sāṃkhya’s dualism might resonate with those who favor a dualist interpretation of quantum mind (consciousness as separate from matter, interacting perhaps via collapse). But all these analogies run into the issue that Indian philosophies were not trying to describe brain mechanics or microphysics. They were addressing questions like “What is self?” “How do we escape suffering?” etc. So a critique is that drawing technical parallels might misrepresent the intent of those philosophies. For example, Sāṃkhya’s puruṣa-prakṛti is a conceptual tool to achieve kaivalya (liberation) by realizing one’s distinction from phenomena – it wasn’t meant to describe neurons. If a neuroscientist says “maybe puruṣa = quantum consciousness and prakṛti = neurons,” it might sound interesting, but a traditional Sāṃkhya master might find it a category mistake.

Explanatory vs Experiential: A notable difference is evidence. Quantum theories can (at least in principle) be tested (e.g. one could test Orch-OR by looking for quantum coherence in microtubules or for proposed EEG signature frequencies). Indian philosophical claims are often verified experientially (through meditation or logical inference) rather than experimentally. For instance, Advaita says “Brahman is bliss”; Buddhism says “all compounded things are unsatisfactory.” These are not falsifiable in a lab; they are more existential truths. So bridging them with science can dilute their meaning. One might critique that attempts to scientize spirituality (e.g. saying “maybe enlightenment is a quantum coherence state in the brain!”) could both undermine the spiritual side (by reducing it to physics) and overreach the science (by trying to explain something it hasn’t the tools to measure – inner enlightenment).

Ethical and practical implications: Indian philosophies of consciousness come tied with ethical and soteriological frameworks – e.g. Buddhist mindfulness is part of an Eightfold Path to reduce suffering; Yoga’s consciousness-liberation is tied to moral precepts (yamas/niyamas). Quantum consciousness theories, on the other hand, are value-neutral scientific hypotheses (Penrose doesn’t claim Orch-OR will make you enlightened or morally better; it’s just an explanation attempt for how consciousness arises). If one tries to use quantum theory to justify, say, the Buddhist view that “nothing has inherent self, so compassion to all is rational,” that’s philosophically beautiful but scientifically quantum mechanics by itself doesn’t entail any ethical guidance (the electron is empty of essence, but that doesn’t tell us to be kind – that guidance comes from the human interpretation and value system). So a critique is that we must be wary of mixing “is” and “ought” across these domains.

Despite these critiques, there is a positive side to this interdisciplinary exploration. Contemporary scholarly views have increasingly taken interest in what Eastern thought can contribute to the science of consciousness. Philosopher Evan Thompson, for example, in “Waking, Dreaming, Being” draws on Indian philosophies (Advaita and Buddhism) in conversation with cognitive science to enrich understanding of the self and consciousness. Neuropsychologist Francisco Varela advocated neurophenomenology, integrating Buddhist mindfulness reports to inform neuroscience. In the realm of physics, some scientists inspired by Vedānta or Buddhism have formulated bold ideas – e.g. Amit Goswami’s “monistic idealism” interpretation of quantum mechanics (he claims consciousness collapses the wavefunction and is the ground of being, citing Vedānta). While Goswami’s views are outside mainstream science, they show the continued allure of bridging these worlds. The Mind and Life Institute, co-founded by the Dalai Lama and Varela, has led to serious research into how meditation alters brain function (with no need to invoke quantum, interestingly – classical neuroscience suffices to measure brain waves of monks). But it has also opened deeper dialogue on the mind’s nature, where sometimes quantum ideas do arise (the Dalai Lama himself has asked questions about quantum measurement in those conferences).

In summary, bridging quantum consciousness and Indian philosophy is a fertile but delicate endeavor. The parallels – observer-centric reality, fundamental consciousness, unity of existence – are real and intriguing. They hint that human intuition (via meditation or philosophy) and scientific discovery (via physics) might be converging on some profound truths about the nature of consciousness and reality. However, one must navigate this terrain carefully, ensuring that similarities are not overstated and differences not glossed over. Each tradition has its vocabulary and context; making them “speak” to each other requires translation, not equivalence.

Conclusion

The exploration of a “quantum brain” in light of Indian spiritual philosophies yields both insights and ironic twists. On one hand, scientific theories like Penrose and Hameroff’s Orch-OR boldly suggest that consciousness is grounded in the quantum realm – a notion that science is rediscovering the primacy of mind that ancient sages long proclaimed. We saw how Advaita Vedānta’s declaration that the world is a projection of one consciousness resonates with the quantum idea that observation brings reality into being. Sages like Schrödinger (a sage of science) explicitly drew the parallel, equating his quantum insights to the Upanishadic “One Mind”. Sāṃkhya-Yoga’s portrayal of a witness consciousness distinct from material fluctuations finds a mirror in the notion of the observer outside the Schrödinger equation, selecting outcomes. Buddhism’s profound insight that phenomena are empty of intrinsic existence and only arise in dependence seems eerily apropos for a quantum world where particles have no definite properties until measured. These parallels are not mere fanciful New Age notions; they are noted by respected thinkers – e.g., the Dalai Lama acknowledging the “dependent arising” in quantum physics, or physicists like Bohm engaging with wholeness reminiscent of Eastern holism.

On the other hand, our investigation also reveals that each tradition – modern science and ancient wisdom – operates in its own domain of discourse. The Orch-OR theory, for all its daring, is a scientific hypothesis that will stand or fall by empirical testing and coherence with physics. Its kinship with Vedānta’s universal consciousness remains metaphorical unless demonstrated by experiment. Conversely, Indian philosophies are not striving to reduce mind to mechanics; they are concerned with truth as experienced by consciousness (what is the self? how to overcome illusion and suffering?). In a sense, they address the qualitative nature of consciousness and its role in the cosmos, while science addresses the quantitative description of physical processes. Bridging them requires acknowledging this difference.

Yet, perhaps both approaches are needed for a full understanding of consciousness. As our knowledge stands in 2025, consciousness remains one of the great mysteries. Standard neuroscience explains correlations (neural patterns associated with experiences) but not why those brain patterns feel like something from inside. Quantum theories like Orch-OR attempt to penetrate deeper, suggesting new physics might be involved – but they are speculative. Indian traditions, through introspection, have mapped out subtle states of mind (from gross thought to pure awareness) and even empirical phenomena like the stages of meditation. They also pose possibilities like consciousness existing beyond the brain (reincarnation, etc.), which science hasn’t validated but continues to probe (e.g. studies on NDEs, etc.). The dialogue between science and spirituality thus remains very much open. Each can potentially enrich the other: science can challenge spiritual ideas to be more precise and to discard claims that don’t hold up (for example, astrology was part of Indian cosmology but finds no support in science); spirituality can challenge science to broaden its paradigms (for example, the success of mindfulness in mental health care has made neuroscience more interested in subjective experience).

In the end, the question of whether the brain operates in a quantum state entwines with age-old questions about the mind’s place in nature. It invites us to revisit ancient wisdom with fresh eyes and to scrutinize modern theories with philosophical depth. Specific interpretations aside, there is a certain poetic convergence: the cutting edge of physics dissolves matter into ghostly waves of probability, while the profoundest Eastern thought dissolves solid reality into a play of consciousness or emptiness. Both point beyond the surface illusion of separateness and solidity. Both hint that the universe we perceive is, in some ways, a response to our inquiry – be it the inquiry of a measurement or of mindful observation.

To conclude, exploring quantum consciousness alongside Vedānta, Sāṃkhya-Yoga, and Buddhism does not “prove” any of them right, but it yields a richer conceptual landscape. It shows that our rational and spiritual intuitions about the mind might be converging toward a more holistic paradigm, one that blurs the line between observer and observed, mind and matter, science and philosophy. Perhaps the ultimate truth of consciousness lies at the intersection of these perspectives – requiring the rigor of science and the insight of contemplative philosophy. As the Upanishads proclaimed and Schrödinger echoed: “sarvaṁ khalvidaṁ Brahma” – All this is Brahman – we might one day say, all this is the unified field of consciousness, known through both equations and enlightenment. Or, in the Buddhist vein, we might realize that when we deeply examine reality, the distinctions we held (particle vs. wave, self vs. other) collapse, leaving a suchness that can be described neither by math nor words, only experienced. Until then, the dialogue continues – a grand, interdisciplinary inquiry into who we are and what this mind is that contemplates itself through both meditative silence and cloud chambers.

References: (as cited in text)

dalailama.com and sources therein.